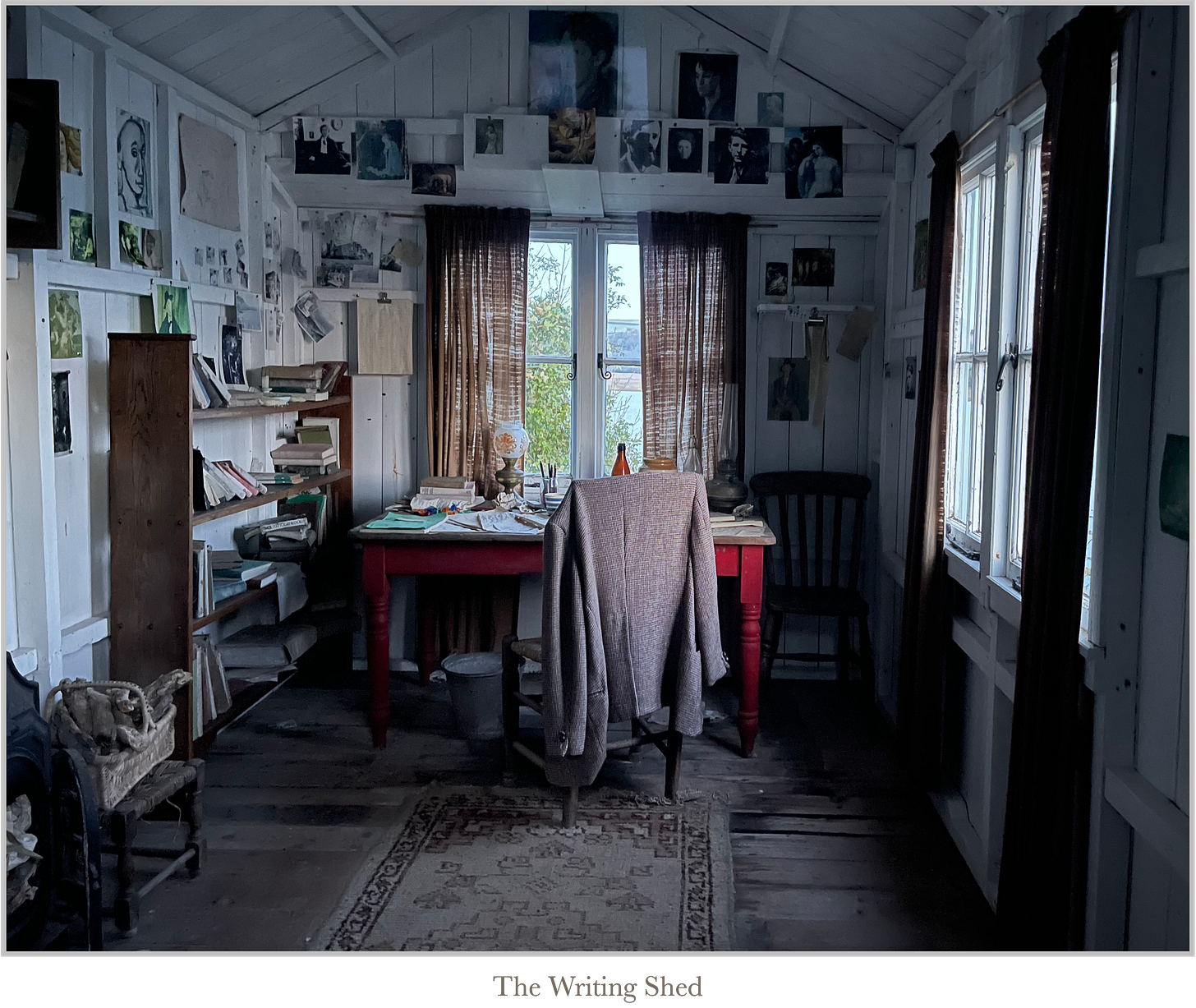

Poetry as Resistance (written in Laugharne) A sweet resistance steals over me to the flow of the hum-drumming, news cycled recycled, same as it ever was, broadcast world. Then there are the noisy, cackle-croaked, black capped castellated rookeries of chatter above my head from the crumbled-down, brown as owls castle. This view of the reed green, sea green marshes and the skittle masted, taking the rising, named hulls of sea breasting boats, in the lap slapped, laid out estuary, that was yours before my time. It has been tourist boarded, info boarded, sign posted to Dylan’s boathouse, the birthday walk, your spoken words on driftwood installations and municipal bench slats. Who has your courage, has your bluster and bombast, to cut through the verbiage, the carnage, the fake outrage to write the seascapes, the estuaries, the channels of our dreams? To articulate a whole town breathing, wreathing, interleaving, reality in a cloudful of lark-song, spark home to love lighting, the children’s feet in yearfuls of streams, the unforgotten tears. That shed you wrote in, smote the page in, walked the wobbly plank of lyrical fidelity in, your spoken pagecraft, that collared our attention, a bright heaven of invention. A life spent ticking the clock round to flashes of lucidity to the high tides of liquidity where words are not weapons but ploughshares to serenity, whispers of infancy, litanies to the ordinary, and keepsakes of eternity. Your writing shed still holds your shape, flyting the lines outloud, the folds of this landscape bare my antipathy to the shackling of words, their captivity by the analytically, media-savvy. I gaze in at the window and recall the old photo I have of Dylan in this hut, gazing at the estuary, willing to break the bread, to be revolutionary, as the vocabulary of his resistance flows into me.

I recently led a retreat at Whirlow Spirituality Centre in Sheffield entitled ‘Entering the round Zion of the Water Bead’ - A Day with the Poet Dylan Thomas. I opened the whole event with the piece above that I wrote a few years ago when in Laugharne, Dylan’s adopted home for a significant portion of his life. Dylan Thomas was a poet of the body, of nature, of process, a war poet (World War Two), and a writer of intense personal nostalgia and incredible humour, a lyricist and a wordsmith.

From the age of fifteen I have been drawn to and influenced by this enigmatic poet whose public persona almost overshadows his work, about whom the legends of drink and debt are numerous and ubiquitous. Laugharne is a sleepy little town on the Gower Coast West of his birthplace in Swansea. When I was a teenager my mother and her boyfriend Maurice had taken me to Ferry side for a holiday with my Auntie Doll for a week or two. Unfortunately Maurice subsequently fell ill and was unable to drive. My Mother was unable to drive the purple Triumph Stag we had travelled downing and so we were marooned! Six weeks we spent in Wales as he recovered , consequently I was well and truly bored. My Aunt and Mother were desperately searching for things to do that would occupy me. I heard that Dylan lived just up the coast and as I was studying him for my English O’Level ( the only one I passed) they drove me to the principality of Laugharne.

I distinctly remember walking to the Boathouse, that he rented for a few years, shared with Caitlin his wife and his children, and that he described in his Author’s Prologue:

This day winding down now

At God speeded summer's end

In the torrent salmon sun,

In my seashaken house

On a breakneck of rocks

Above the house is a little garret or garage that he converted into a writing shed. As a distracted and trouble teenager I looked into this den of poetry and creation and a strange and yearning desire for the writing life awoke in me.

Sadly the urge was fleeting and my life went in other directions but I never forgot that room or the poems and writings of that first poetic superstar. He was one of the first to recognise and exploit the medium of radio at the BBC. He was recorded and sold thousands of records. Here he is reading Poem In October that so beguiled me.

The fire that was briefly kindled in 1976 rekindled again in 2001 when I turned fifty and made a pilgrimage back to Laugharne and began to try and to make a life of writing poetry. I recorded the whole thing in a poem called Visits to Laugharne at Fifteen and Fifty .

They say a glimmer in the teens can

glisten at fifty, so here in his house I

stir the cog and whir of running verse,

winding again the spent spring of youth,

then later standing high at the end of his

birthday’s walk staring back down

age’s track, all seasoned by Dylan’s

visceral candour, and his October blood.

I have tried, following in his steps to walk ‘the wobbly plank of lyrical fidelity’. I think that writing poetry, as I say in the poem at the head of this, can be an act of resistance. A good poem allows the writer and the reader to enter the round Zion of their own imagination and pray in the synagogue of the ear of corn that is their own story and inner mythology. If you read the poem that these ideas are from you will see what I mean. it is one of his war poems about the blitz.1

‘A good poem is a contribution to reality. The world is never the same once a good poem has been added to it. A good poem helps to change the shape of the universe, helps to extend everyone's knowledge of themselves and the world around them.’ Dylan Thomas

As my friend David Whyte says ‘this is the time of loaves and fishes. People are hungry, and one good word is bread for a thousand.’ Dylan struggled to keep his head above water, financially, psychologically, relationally and in terms of his drinking, but his words were and are bread for thousands. His daughter Aeronwy and his wife would lock him into the writing shed as his words were their only source of income. Here is what she says in a beautiful memoir about him.

‘I always knew whether my father was working or reading his forbidden detective novels. If you passed and heard nothing he was reading, for as soon as he picked up his fountain-pen he spoke every word out loud. For him, the sound of the words was integral to the poem. Sometimes his voice was loud and booming, at other times I had to put my ear to the thin door to hear his mumbles. It seemed like a secretive, incantatory rite.’

Aeronwy Thomas, My Father's Places

I want to keep at the process of these secret incantatory rites and then share them in a way that builds up the inner fires of sweet resistance.

Lovely, thank you!