A Worn-Out Pit Pony It hangs among the views of pitmen’s lives, captured by men who spent years in blackness, then came up into the vivid light, donned suits, shirts and ties and painted what they saw. You could miss it in the jumble of works rendered with, and on whatever medium could be found in a pit town and by men who had their families to feed and clothe. It isn’t large and it needs a second look, as do many of these works, not done by the smock suited, art schooled denizens of London’s fashionable airy ateliers. It was painted in a wooden hut or hall, Ashington Art Group plated on the door. A place where they found an outlet, a self-ordained font of creative freedom. It comes from a man’s youthful memory, that remerged when his collier father lost his fight to breathe and the coroner moved to declare him a worn-out pitman. The pony in the poignant, tender painting stands for a miner’s father, a creature's lifetime in the dark, and as I stand in front of it now, stands for an industry that died in front of me. This all sounds like an easy metaphor, one thing standing for another, until your heart breaks when you look into that tub long enough to grasp what abandonment feels like. Written in honour of the painting by Fred Laidler - Dead Pony in the Woodhorn Museum Ashington Northumberland

I have been working on this poem for a few weeks now. It is another that will form part of my next collection - the working title of which is Grim Up North. Our podcast of the same name has given me so much material. For the final episode of the first series entitled Seeing the North, all about northern art, we took a trip to the Woodhorn Museum in Ashington - Northumberland. It houses both a mining museum and a collection of paintings by a group of miners known as the Pitmen Painters.

You can listen here to a great interview with Vicky Jones, one of the guides at the museum as she shows us around the room dedicated to those quietly impressive men. Their brush strokes - with cheap materials on any hard surface that came to hand, are testament to a vision of the world gained at the cost of working lives spent in darkness.

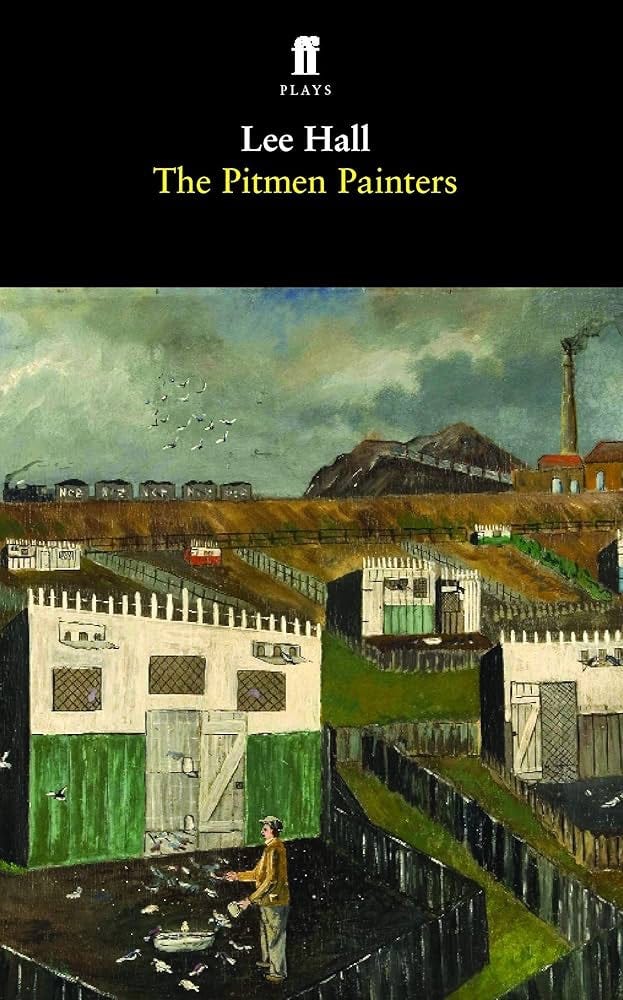

If you want a sense of these men read (or watch - if it plays near you) Lee Hall’s Pitmen Painters. He is the writer of the far better known Billy Elliot. The tale that the exhibition and the play tells is of a group of miners (employed and unemployed) who availed themselves of the opportunities afforded by the Worker’s Education Association (WEA) in 1930’s. Founded in 1903, their mission is to bring adult education within reach of everyone who needs it. In Ashington at that time they offered such education to men who would have been contemporaries of my Father who grew up there and was born in 1910.

They opted to study Art Appreciation and Robert Lyon of Durham University, an art lecturer, was sent out to instruct them. Having failed to catch their attention with a magic lantern show on renaissance art he decided to take art materials so they could learn by doing. They began with lino-cuts and then moved slowly onto painting. They portrayed what they saw everyday, pit heads, underground, whippets and pit houses. To wander the exhibition is to enter a way of life that no longer exists in this country. It is as much an act of social anthropology as it is art appreciation.

My poem is an angry paean to the industry my father grew up around, many of his friends and family were miners and the industry I watched being decimated in the 80.s and 90’s living in South Yorkshire. It is not that I would want to go back to a carbon dependent past or have people subjected to the privations and stresses of mining. The point is that the towns and villages that grew up around the pits had a culture of dignity and power that was purposely destroyed with no thought as to the fate of these incredible people. They were dubbed, by the arch vandal of the coalfields and the life they nurtured - Margaret Thatcher, as The enemy within!

It was deemed perfectly acceptable to leave them in penury as a punishment for attempting to preserve their livelihood. All this with no offer of any alternative. It is still affects this area and the North East today. As those that lived through it age and die they should never be forgotten and the museum in Ashington is well worth a visit, to both pay homage and remember. 1 I would also urge readers to listen to this piece of music. Written by Robert Saint it has now become a fitting musical tribute to the worn out pit pony that was British mining.