Evacuee

Poems and Thoughts from the Anxious Poet

Evacuee

I imagine you standing there on the platform

with your label and your gas mask strung over your shoulder,

excited to be travelling, chattering with friends.

Then tearful, startled at that first shunting movement

as the train judders, gasping steam, pulling you away from home,

away from the blitz and the bomb laden skies over London.

I still have your label, posted back from Northampton,

the first hard evidence reaching my Grandparent’s doormat

of your safe arrival in unfamiliar lodging, such a gap of waiting.

Now when I locate a sudden departure in my life,

where the present state of things demands a moving on,

I pray to that little evacuee, the Mothering all latent in her

child’s womb, yet to be born from war’s labour and my delivery.

Now, again, you have been evacuated and I have received

no hand-written label, no assurance of your safe arrival.

What do I tell your Grandchildren still missing the woman

who sang them songs from the war, with calm assurances of peace?

Is it perhaps that the lengthening gap of absence, the empty chair

that must have filled your own Mother’s Willesden terrace

and now sits in the corner of our unvisited Sunday afternoons

is your presence, rendering our deliveries and departures hopeful?

Does absence becomes presence, a sacrament of holding—

latent as I evoke you now and a young girls hand slips into mine?

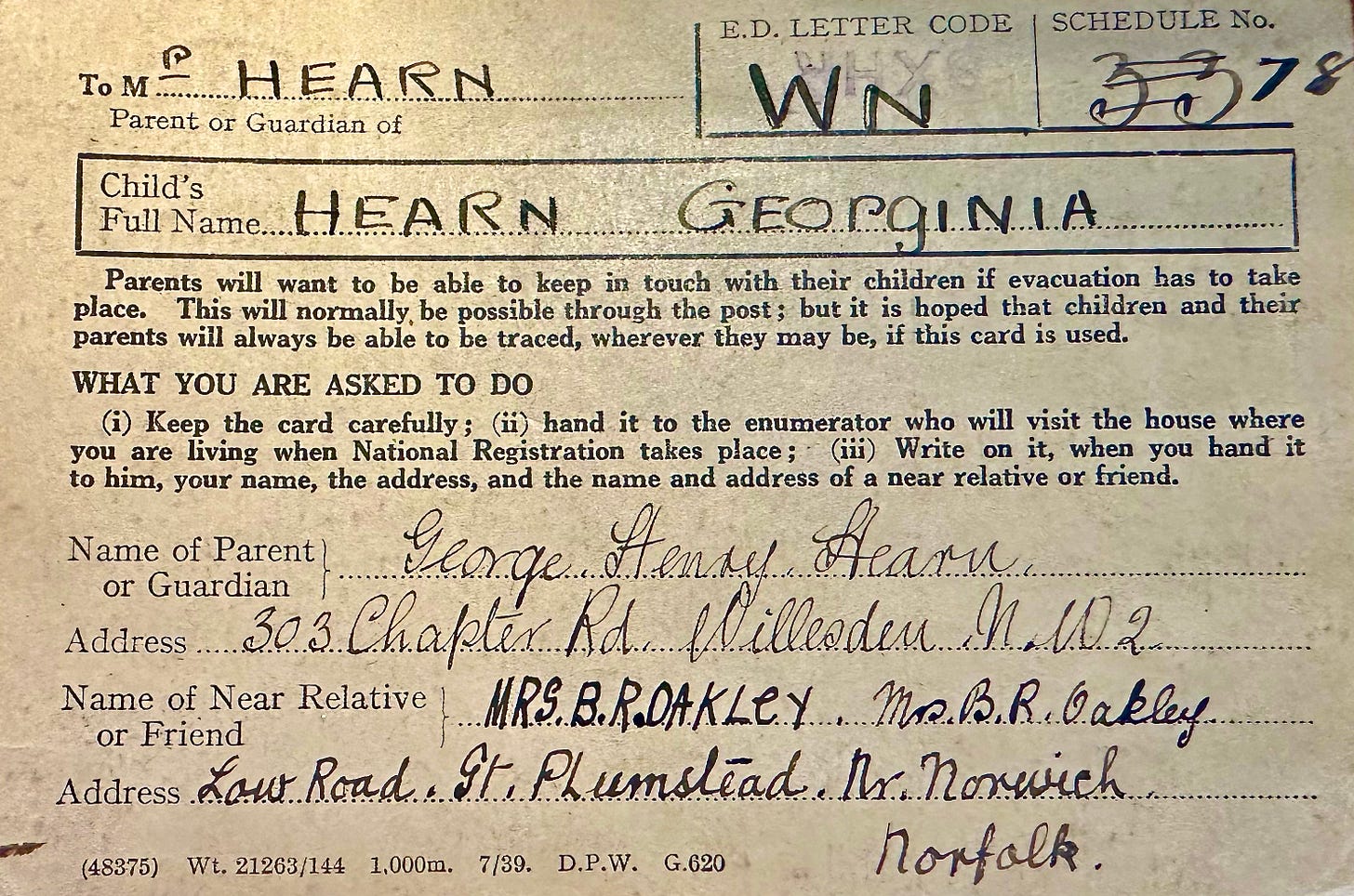

I have just released the latest Anxious Poet’s Podcast on the theme of Naming our Myths - during which I spoke of the fact that we are moving house and therefore I had been going through boxes of accumulated stuff. One of the artefacts that I was speaking of, in terms of forming my personal narrative and mythology was my Mother’s evacuation card. (see below)

Then I remembered that I had written this poem about my Mother’s evacuation and I thought it would make a good addendum to the podcast. This part of my family story made a deep impression on me. Millions of children were sent away from the big cities in 1939, to save them from the impending blitz. My mother was such a one - although she thought she was going to Littlehampton by the sea, in fact it was Northampton. She was nine years old and my Grandmother took her to a station with a label attached to her with her name and adress and the next she heard was when the host family posted the label back to her. After six weeks had passed my Grandmother went to visit and found her unwashed and unhappy and brought her back to Chapter Road in North London where they all spent the rest of the war.

She had a few hours at school a week and the rest of the time studied at home. Her stories of collecting shrapnel after raids, sleeping in the Anderson Shelter at the bottom of the garden, of my grandfather keeping chickens were a source of fascination to me. My grandfather George Henry Hearn was a fire warden and unfortunately, died three weeks after I was born in 1961. My Mum remembered that he was particularly squeamish and one day they decided to have a treat and kill one of the chickens. He got a hatchet and held the bird on the step and did the deed. His daughter was far less bothered and watched with mawkish glee as the headless chicken ran off down the garden as her father threw up!

There were more sobering stories though. Her chilling memories of the Anti-Aircraft gun that would traverse the railway line behind the house firing at the German bombers. Or the direct hit on the next door neighbours that took a number of lives.

In Dylan Thomas’s magisterial poem A Refusal to Mourn the Death, by Fire, of a Child in London he speaks of the all humbling darkness and the majesty and burning of the child's death. In many ways Dylan was a war poet and he gives voice to the shadow that lurks in my family narrative and myth - that of the Second World War. It shaped the attitudes of my mother and grandmother which could be summed up in the phrase ‘you just get on with it.’ If I asked about how they dealt with all that trauma this was their mantra. I think it took its toll and certainly for my mother left a residue of depression.

It also made her very resolute in the face of dark times, she conveyed a great sense of safety and doughtiness that my kids deeply valued and missed when she died in 2006. Her absence created a sense in us of her ongoing presence in our family myth and story. And whenever we hear the song ‘We’ll Meet Again’ by Vera Lynn we feel her near us.

This photo is of her with my Auntie Julie - her sister and her friend Midge (I think). She joined the Wrens not long after the war and again I wonder if this was another effect of the conflict and its militarisation of the country. These actions also led to her meeting my Father. He was a Naval Officer stationed in Helston in Cornwall - HMS Culdrose. She was assigned to serve in the wardroom where the officers ate and he noticed her propensity to blush and cover it with her hand over her face and neck and he mimicked her. She was furious and yet somehow resentment turned to love and they were married in the early 1950’s.

All of these narratives form my personal myth and I tried to convey that in the poem. The way this has all come down to me. I also found the idea that all a women’s eggs are present in them from birth compelling - the potential me in that little girl. Finally I love the notion that the little evacuee that was my mother acts like a patron saint in my life especially when I experience losses and sudden departures. All with the hint of an assurance that we may meet again.